1. Current Situation

The work on harmonising environmental requirements falls under the national Secretariat’s operational focus on contract monitoring. Within the framework of contract monitoring, the Secretariat and the regions already follow a national process, from the identification of risks and opportunities to the establishment of common requirements and contract follow-ups.

The harmonisation work has progressed significantly regarding requirements, guidance, and contract monitoring in certain areas, such as sustainable supply chains, systematic environmental work, and, more recently, guidance on applying sustainability criteria within pharmaceuticals. Work is also ongoing to harmonise common Nordic packaging requirements for healthcare products.

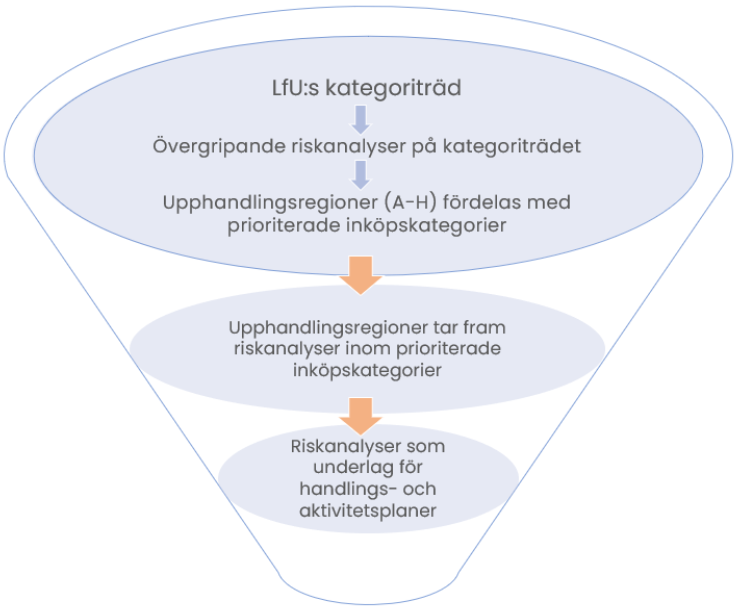

A comprehensive risk analysis of procurement categories, based on the LfU category tree, has been conducted to identify priority categories according to social and environmental sustainability risks, as well as anti-corruption risks.

The national process is illustrated in Figure 1. The Secretariat currently works with procurement regions A–H (1), focusing on approximately 20 priority procurement categories.

(“Procurement regions” is LfU’s term for the regions that collaborate on procurement matters, with representation in various groupings based on size and geographical location.)

Illustration: National Secretariat for Sustainable Procurement

Action plans are developed for each procurement region (A–H) with a three-year perspective, revised annually, to ensure purposeful long-term planning in priority areas. Operational activity plans are set on an annual basis and include market analysis, in-depth analyses of product groups to better understand sustainability risks and opportunities, improved requirement setting, and prioritisation of products for nationally coordinated contract monitoring.

Rather than creating parallel processes, the harmonisation of environmental requirements should integrate and build upon existing practices. This includes, in particular, integrating guidance and criteria development as well as the contract monitoring of environmental requirements into action plans in a more structured and systematic way, with support from the Secretariat.

1.1 Sustainable Procurement and the Swedish Public Procurement Agency

Upphandlingsmyndigheten, UHM, provides procuring authorities with support in the form of voluntary sustainability criteria for procurement. In accordance with its mandate, UHM works to increase environmental and social consideration and to develop and maintain sustainability criteria within procurement. The agency also manages a national criteria database, for example for environmentally adapted procurement.

The joint strategy for harmonising environmental requirements in public procurement across Sweden’s regions is not intended to replace UHM as the national hub for sustainability criteria. Rather, the strategy should be seen as a complement to UHM’s services, aiming to develop environmental criteria and application support within priority procurement categories under the regions’ national collaboration on sustainable procurement. Development efforts should focus where environmental criteria are completely missing or not up to date at UHM, and where there is a need for application support to harmonise existing criteria.

In the long term, a possible outcome of the environmental requirement harmonisation strategy could be that UHM takes over the management of these criteria in collaboration with the regions. Table 1 shows a mapping of the regions’ priority procurement categories against UHM’s existing sustainability criteria. The table clearly indicates which priority categories have support from UHM and where gaps in criteria support exist.

| Procurement Regions A-H* | Prioritised purchasing categories (Area of Responsibility) | UHM Criteria Available (Yes/No) | Number of Criteria |

| A | General Consumables in Healthcare (including surgical instruments, healthcare-related paper and plastics, n.2–3**) | No | – |

| A | Medical Basic Equipment (n.2) | Unclear – general criteria exist, see “Other” | – |

| B | Food & Related Services (n.2) | Yes | Over 100 |

| B | Facility Cleaning (n.2) | Yes | 38 – 52 |

| B | Nutrition (n.2) | No | – |

| C | IT & Communications (n.1) | Yes (computers/monitors) | 26 |

| C | Medical Technology Equipment and Related Consumables, IT Imaging and Function (n.2) | Unclear – general criteria exist, see “Other” | – |

| D | Wound Care and Compression (n.2) | No | – |

| D | Dental Equipment and Consumables (n.2) | No | – |

| E | Pharmaceuticals (n.2) | Yes | 9 |

| F | Incontinence & Stoma Care (n.2) | No | – |

| F | General Healthcare Consumables (including medical chemicals, gloves, and other surgical items) (n.2–3) | Yes (gloves) | |

| G | Anesthesia (Medical Technology) (n.2) | Yes | 1 |

| G | Surgery (Medical Technology) (n.2) | No | – |

| G | Therapy & Diagnostics (Medical Technology) (n.2) | Yes | 21 |

| H | Furniture (n.2) | Yes | 28 |

| H | Laundry and Textiles (n.2) | Yes | 15 / 13 |

| Other | |||

| UHM Category “Medical Consumables” – 15 general criteria that may be applicable across various procurement categories listed above. | 15 | ||

| In total, approximately 280 of the identified criteria from the mapping can be applied within the regions’ priority procurement categories. The highest number of applicable criteria is found in Area B, with over 150, primarily within food. However, many of the regions’ priority procurement categories still lack criteria, meaning there is currently no national support for these. | Total: approx. 280 | ||

1.2 Environmental Focus Areas

In 2018, the Steering Group of the Secretariat decided that the environmental focus areas for sustainable procurement should be a non-toxic environment (reducing the spread of health- and environmentally hazardous substances), reduced climate impact, and circular economy. These areas align well with the regions’ own environmental and sustainability work in governing programs as well as with national strategies. The areas are described in greater detail in Appendix A.

2. The Path to Harmonised Environmental Requirements

To realize the strategy’s long-term goal of having harmonized environmental requirements and application guidelines across all prioritized procurement categories, processes and working methods need to be developed and integrated into the support provided within the national collaboration.

The working methods and processes are project-managed by the national secretariat in consultation and collaboration with the regions and the steering group. The actual implementation is the primary responsibility of each participating region within its procurement region. The overall processes are illustrated in Figure 2.

FIG 2 Development, implementation, and evaluation…

IMAGE MISSING

Figure 2 Processes for harmonizing the regions’ environmental requirements in procurement

Illustration: National Secretariat for Sustainable Procurement

2.1 Environmental Prioritization of Product Groups

To work effectively with the harmonization of environmental requirements, product groups need to be prioritized within each procurement category (4). The development of criteria and application support (5) for environmental requirements should be carried out where the greatest possible positive impact can be achieved, based on available resources.

4 A procurement category encompasses a broader group of goods and services at an overarching level, while a product group includes a group of goods with similar characteristics. For example, “IT and communication” or “IT workplace” are procurement categories, while desktop and laptop PCs, monitors, thin clients, and telephones are product groups. Procurement categories and product groups are often organized according to the supplier market and purchasing patterns of the organization.

5 The criteria consist of pre-formulated requirement texts with accompanying information, such as how the requirement should be verified or evaluated. Application support complements the pre-formulated requirement texts, which to varying degrees may be complex, by providing guidance on how, why, and when the criteria should be applied, as well as how they should be evaluated or followed up.

The Environmental Prioritization Model Should Be Based on at Least:

- LfU’s category tree

- Risks and opportunities within all environmental focus areas from a life-cycle perspective

- Assessment of the availability of established environmental requirements

- Relevance, potential for change, and degree of controllability

Over Time, the Following Should Also Be Considered:

- Spend per procurement category/product group (SEK)

- Order volume (number of units)

- Complexity of the product group/product

- Availability of data for evaluating or conducting life-cycle analyses

- Market maturity for more sustainable products and business models

To move into action in the planning work of the procurement regions, the final selection of environmentally prioritized product groups should be integrated into the existing process for developing three-year action plans and annual activity plans. Which environmental areas are most urgent to develop requirements within should be based, among other things, on the environmental prioritization assessment.

2.2 Criteria Development and Application Support for Prioritized Product Groups

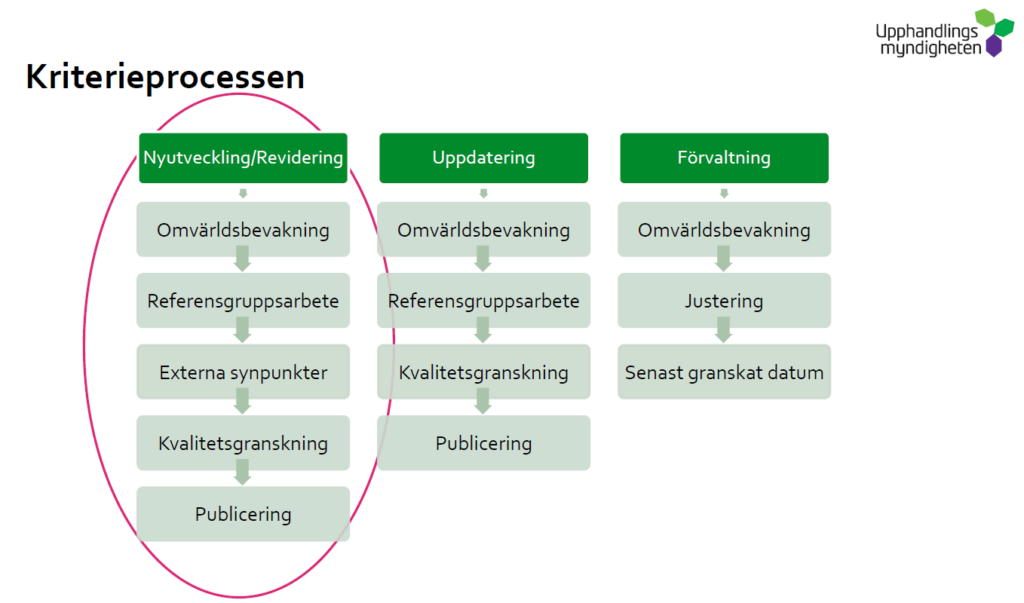

To develop documents containing harmonized criteria and application support that the regions can implement, a standardized process is required. This process should, in broad terms, follow the Swedish Procurement Authority’s process for criteria development and revision (Figure 3), with certain adaptations—such as enhanced and continuous market dialogue. The final product, consisting of criteria and application support, should be produced according to a predefined template, completed by the working groups responsible for developing the criteria.

Illustration: Swedish Procurement Authority

Supporting guidelines shall be developed by the Secretariat in collaboration with the regions to standardize the implementation of risk analyses, market analyses, supplier dialogues, criteria development, and consultation management. Well-executed market analyses and supplier dialogues are particularly important in connection with criteria development.

A screening should be the first step before the development work begins in earnest. The purpose of the screening is to quickly identify a starting point and determine whether established requirements already exist for a selected product group.

There are two main paths forward depending on the screening results:

- Existing, updated, and relevant environmental criteria exist within the prioritized procurement category at the Swedish Procurement Authority or another trusted actor → Develop implementation guidance for existing criteria, and if needed, develop new criteria as a complement to the existing ones.

- No existing environmental criteria exist at the Swedish Procurement Authority or another trusted actor → Primarily follow the process flow in Figure 3 for new criteria development and monitor recent procurements in the contract area to capture the latest experience of requirement-setting and market conditions.“Another actor” refers to an established, independent party trusted in the field, such as the European Commission (EU GPP criteria), IVL’s Kriterieklivet, Health Care Without Harm (HCWH), Global Green and Healthy Hospitals (GGHH), or environmental labeling organizations (Svanen, EU Ecolabel, TCO Certified, etc.).

Table 1, mapping the regions’ prioritized procurement categories against the existing environmental criteria of the Swedish Procurement Authority, provides an overview of which procurement categories have criteria available from the UHM library and which currently lack criteria.

Resource and time requirements will vary greatly depending on whether environmental criteria already exist or not. If criteria already exist, implementation guidance can in some cases be developed relatively quickly, whereas developing new criteria is expected to require significantly more resources and time.

Harmonization work assumes a common ambition base with minimum requirements that serve as the regions’ shared baseline for procurement within prioritized product groups. This forms a floor of requirements that suppliers must meet. At the same time, collaboration should allow for the development of harmonized environmental criteria at advanced and cutting-edge levels that regions with higher environmental ambitions can also apply consistently – ensuring these regions do not fall entirely outside the harmonization work.

Environmental harmonization work should be based on shared principles for baseline criteria:

- Simple and clear, as far as reasonably possible

- Environmentally effective and purposeful to drive change

- Well-considered and predictable for the market

- Verifiable, assessable, and follow-up capable

- Aligned with the functional needs requested by users

- Legally and linguistically reviewed

To ensure that the criteria developed are reasonable in relation to what is being procured and do not otherwise conflict with procurement law principles, they should also undergo legal review.

Advanced and cutting-edge criteria are also encouraged to adhere to the above principles as much as possible. While harmonized baseline requirements form a shared national floor, it is equally important that advanced and cutting-edge criteria are harmonized wherever possible to promote and reward innovative solutions progressing in the desired direction.

Too many dispersed advanced criteria within a procurement category or product group can risk predictability for the market, potentially leading to more costly solutions and making it harder for suppliers to achieve economies of scale, which in turn increases procurement costs for the regions. During future criteria revisions, requirement levels can be tightened as market maturity develops.

Opportunities to coordinate development work in certain procurement categories with other supporting and procuring authorities or collaboration partners of the national Secretariat for Sustainable Procurement should also be leveraged (e.g., Kammarkollegiet and Adda procurement center). This enables greater harmonization of requirements and synergies in resource use. Furniture and IT & Communication are large enough procurement categories that opportunities for coordinated work are particularly evident.

There is also potential to coordinate and collaborate on the development of procurement categories within healthcare at the Nordic level with partners in Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland.

Type 1 eco-labels (such as Svanen, EU Ecolabel, Bra Miljöval, KRAV) developed according to ISO 14024 (7) are also an important instrument to consider when developing criteria and implementation guidance. Clear criteria facilitate suppliers in submitting bids against clearly stated environmental requirements and create incentives for eco-label organizations to eventually expand the range of product groups that can be eco-labeled.

7. This international standard contains principles and procedures for developing Type I ecolabel programs, including the selection of product groups, environmental criteria, and functional requirements, as well as for assessing and demonstrating compliance. The standard also includes the certification procedures required to obtain the license.

When Type I ecolabel criteria are used, the need for contract follow-up is met through the ecolabel organization, which conducts inspection visits before issuing the license. What remains for the procuring authority is to verify the license’s validity throughout the contract period, although this process may eventually become automated.

2.3 Implementation of Harmonized Environmental Requirements

The national office for sustainable procurement serves as a support function for all regions, but it does not have its own mandate to enforce adoption within the regions. For the harmonization of environmental requirements through joint criteria and implementation guidance to have any effect, it is entirely dependent on the requirements being implemented within the regions.

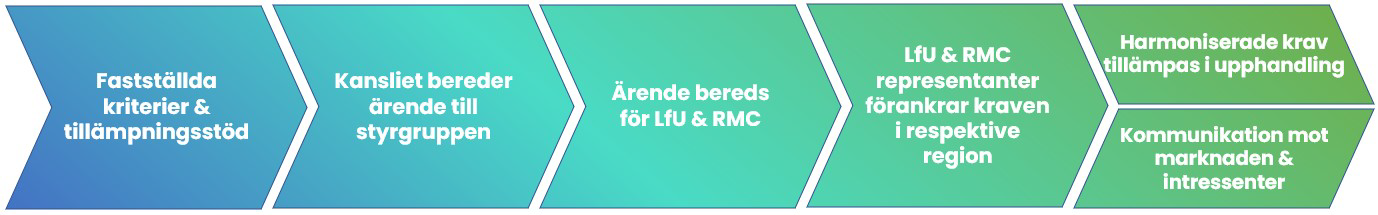

This anchoring process requires shared responsibility between the regions’ representatives in LfU and RMC, who commit to informing and providing clear directives to the operational procurement units within their respective regions to apply the harmonized requirements at least at the baseline level.

Communication of newly developed criteria and implementation guidance is also important for many stakeholders, not least suppliers, the regions, and other collaboration partners. There are many ways to communicate, including launch webinars, news on the office’s website, newsletters, and email distributions to suppliers and industry organizations.

Figure 4 illustrates the overall flow from when criteria and implementation guidance are finalized to their application in the regions’ procurements and broad external communication.

Illustration: National Office for Sustainable Procurement

2.4 Contract Monitoring of Harmonized Environmental Requirements

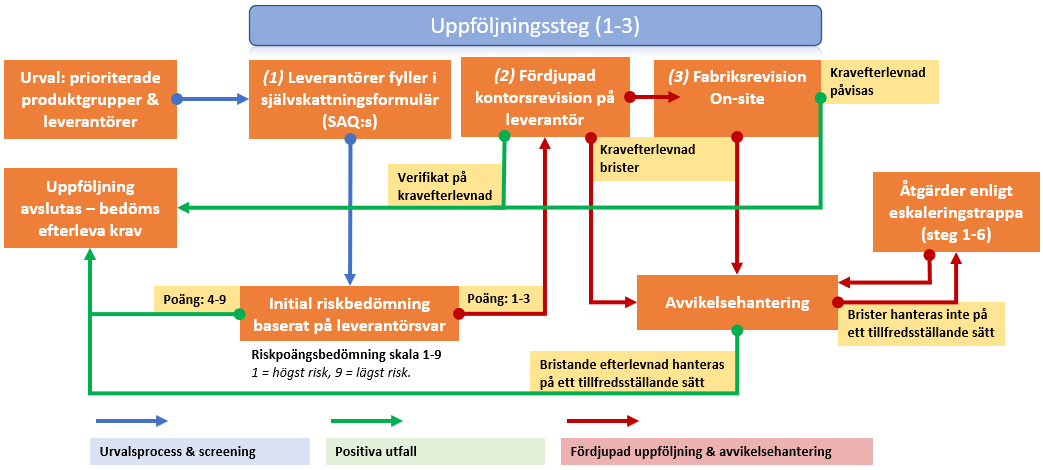

Harmonizing environmental requirements is a prerequisite for carrying out nationally coordinated follow-ups. For several years, the National Office and the regions have conducted nationally coordinated follow-ups on contract terms related to sustainable supply chains and systematic environmental management. The sustainability requirements monitored nationally within selected product groups are those prioritized in the risk areas’ action plans.

Apart from requirements for systematic environmental management, nationally coordinated follow-ups on environmental requirements are currently lacking, as the conditions for this are not yet in place, given that the regions have not yet agreed on harmonized environmental requirements within the prioritized procurement categories.

In cases where the same requirements already exist, for example through the use of the Swedish Public Procurement Authority’s (UHM) environmental requirements, a consolidated overview (common contract register) of these requirements among the regions is needed. Without this, there is no basis for coordinating follow-ups on these contracts. The same overview of contracts with established common environmental requirements will be necessary for resource-efficient coordination in contract monitoring, ensuring the proper conditions to work effectively and purposefully.

Currently, national follow-ups are conducted via the Worldfavor system within an existing follow-up process with associated routines, see process in Figure 5. Rather than developing a parallel process, the existing follow-up process needs to be updated to integrate the monitoring of environmental requirements that will be followed up through national coordination.

Illustration: National Office for Sustainable Procurement

The conditions for monitoring environmental requirements differ from those for following up on supplier management conditions (sustainable supply chains/systematic environmental management), as they largely relate to the product’s performance or technical specifications. This introduces greater variation in the requirements that need to be monitored and evaluated.

This complexity in follow-up must be considered and synchronized within the monitoring routines when developing the criteria and guidance documents, specifying the methods and support for follow-up. If needed, additional follow-up processes for environmental requirements will be developed.

A good example of successful collaboration is KemKollen (8), a national coordination platform for monitoring chemical requirements. Here, focus areas are selected, and a stakeholder group from regions and municipalities chooses products within their own contracts, which are then sent for chemical analysis coordinated by Adda. In KemKollen, Adda, several regions, and the National Office for Sustainable Procurement have participated in investigations, product selection, and compilation of chemical content, including in focus areas such as household goods and healthcare products.

8. (Source: KemKollen 2020)

2.5 Management and Evaluation of Criteria and Implementation Support

The criteria and implementation support documents shall be managed and revised by each procurement region within their responsible procurement categories (according to the applicable division of responsibilities), with support from the National Office and a management plan. The management plan outlines how the criteria are kept up to date. All criteria and implementation support documents shall be made available on the National Office’s website, www.husr.se, this website. In the long term, ownership of the criteria and implementation support could, in dialogue with the Swedish Public Procurement Authority (UHM), be transferred to the authority for a centralized repository of sustainability criteria. Such collaboration offers several advantages:

- Greater impact of the criteria through use by other contracting authorities

- Reduced workload for the regions and the National Office within the national collaboration

- Closer cooperation between the National Office, regions, and UHM in priority procurement categories, leading to a better understanding of each other’s needs

It is crucial to keep the criteria and implementation support updated and relevant to the current market situation. Some markets have rapid innovation and product development cycles, while others develop more slowly. It is therefore important to keep the criteria relevant. At the same time, it is important to evaluate the use of the criteria and implementation support based on practical experiences in regional procurements. This evaluation serves two purposes: to capture lessons learned for improving the criteria, and to assess how many regions apply the common environmental requirements in new procurements. A standard revision interval of three years is recommended.

The strategy applies a PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) cycle as the framework for all processes (Figure 6) to ensure a structured and systematic approach that effectively achieves the objective—creating relevant and monitorable harmonized environmental requirements within priority procurement categories applied in regional procurements. The processes align with the PDCA cycle as follows:

- Environmental prioritization of product groups – Plan

- Criteria development and implementation support for prioritized product groups – Do

- Implementation of harmonized environmental requirements – Do

- Contract follow-up on harmonized environmental requirements – Check

- Management and evaluation of criteria and implementation support – Check/Act

Illustration: National Office for Sustainable Procurement

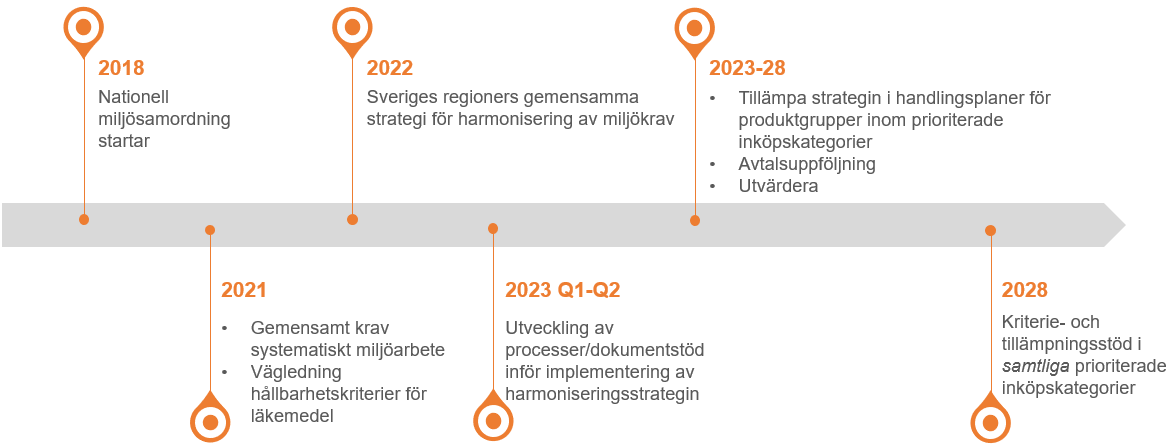

3. Timeline and Preconditions – Roles, Responsibilities, and Implementation

Both the development of the above processes and routines, as well as the implementation of the strategy, require resources in terms of both time and money. The work must be aligned with a realistic timeline to carry out the mapped activities in the strategy based on the resources available annually.

Timeline

The strategy’s timeline aims to have criteria and implementation support in place for all prioritized procurement categories by the end of 2028, providing six years to work on the harmonization effort starting from 2023. See the timeline in Figure 7. This implies an average production pace of developing criteria and implementation support for 3–4 procurement categories per year.

With an average production pace of 3–4 criteria and implementation supports per year, not all eight procurement regions need to work continuously in parallel on criteria development. Through product group prioritization and cross-area collaboration, the regions’ combined resources can be concentrated in temporary project groups until the criteria and implementation support documents are finalized.

Illustration: National Secretariat for Sustainable Procurement

Roles, Responsibilities, and Implementation

Table 2 outlines which guiding and governing documents, in their various forms, need to be established, as well as the distribution of responsibilities for the development and application of each process step.

Table 2 Document Governance Needs, Roles, and Responsibilities

| Process | Document governance needs | Developed by | Executed / applied by |

| Environmental prioritisation of product groups | • Environmental prioritisation model • Risk analyses | Secretariat / Environmental prioritisation working group | Regional coordinators & environmental contact persons |

| Criteria development & implementation support | • Guidance documents for development of criteria and implementation support • Template documents for criteria and implementation support | Secretariat, in collaboration with the regions | Regional coordinators & environmental contact persons |

| Implementation of harmonised environmental requirements | • Procedure for anchoring and communication | Secretariat, in collaboration with the regions | Secretariat, LfU & RMC |

| Contract follow-up of environmental requirements | • Follow-up of environmental requirements integrated into the existing monitoring process | Secretariat, in collaboration with the regions | Regional coordinators & environmental contact persons |

| Management and evaluation | • Procedure for management & evaluation of requirements, including a management plan • Procedure for impact reporting with KPIs | Secretariat, in collaboration with the regions | Secretariat, regional coordinators & environmental contact persons |

Genomförandet av strategiarbetet görs inom befintliga ramar och resurser enligt de som beskrivs i Programförklaring 2030 där varje region har ett stort eget ansvar att resurssätta arbetet.

4. Appendix A – Environmental Focus Areas

Non-toxic environment

To protect human health and biodiversity, the spread of substances hazardous to health and the environment must be prevented and reduced. Chemical substances can cause acute harm or long-term damage, for example by being carcinogenic, mutagenic, reprotoxic, endocrine-disrupting, or environmentally hazardous. The use of antibacterial substances, such as biocides, can lead to antibiotic resistance, meaning bacteria develop resistance to antibiotics. This is a serious and growing public health issue both in Sweden and globally.

The goal of a non-toxic environment, with reduced spread of hazardous substances, is strongly linked to Agenda 2030 and several global sustainability goals.

Setting chemical requirements in procurement is an important tool to phase out dangerous substances and thereby contribute to reducing negative impacts on humans and the environment. Traditionally, the regions have set extensive requirements regarding the content of hazardous substances in procured products, but there has been significant variation in how these requirements have been applied and what type of verification or evidence has been accepted.

To drive progress towards a non-toxic environment, it is important that the regions harmonise their requirements within this focus area across the prioritized procurement categories.

Reduced climate impact

Climate change is one of the most pressing issues of our time, and global warming has catastrophic consequences for the Earth and its inhabitants. The climate system is complex, and an increase in global average temperatures leads to changes that trigger new negative effects. Global warming contributes, for example, to glacier melt, rising sea levels, increased flooding, and more frequent and intense extreme weather events such as storms, wildfires, and heatwaves.

Humans, animals, plants, their habitats, and entire ecosystems are threatened. One of today’s greatest challenges is therefore to reverse the trend of increasing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid or mitigate increasingly severe impacts and serious disruptions for both people and nature.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its Sixth Assessment Report (released in three parts between 2021–2022), has shown that rapid emission reductions are necessary. To achieve the 1.5°C target of the Paris Agreement, global emissions must begin to decline before 2025 and reach net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2050.

The remaining global carbon budget to meet the 1.5°C target is approximately 460 billion tonnes of CO₂. At the current rate of emissions, this carbon budget will be exhausted in about 11.5 years.

Goal 13 of Agenda 2030 focuses on reducing and limiting negative climate impacts. The Swedish Public Procurement Agency’s environmental spend analysis (external link) of the regions’ environmental impact from procurement, based on 2019 data, shows that emissions amounted to 6.1 million tonnes, corresponding to 24 per cent of the total climate impact from public procurement in Sweden that year.

Although public transport, other transportation, and buildings constitute a large part of a region’s climate impact, the goods procured for healthcare also account for a significant share of the total climate impact.

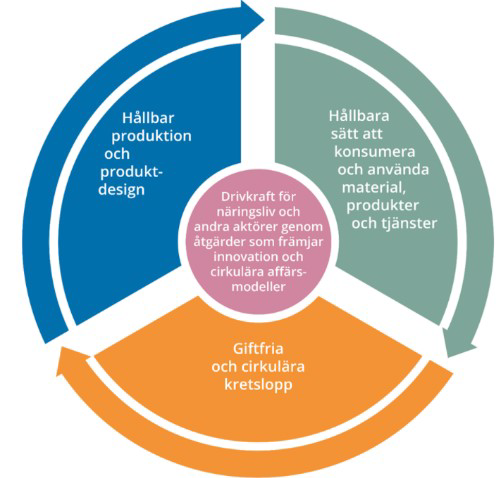

Circular Economy

The circular economy is a production and consumption model focused on reusing, repairing, refurbishing, and recycling existing materials and products to keep resources circulating within the economy wherever possible. In a circular economy, waste itself becomes a resource, which minimises the amount of actual waste generated. (Circular economy: definition, importance and benefits | News | European Parliament (europa.eu))

The circular economy is therefore a tool to reduce our resource use and, in doing so, limit climate and environmental impacts by moving from a linear to a circular model that conserves the Earth’s resources.

Products in a circular economy should be designed to be easy to reuse, upgrade, repair, and recycle. Biological materials should be compostable. Achieving a sustainable and successful circular economy requires the phasing out of hazardous chemicals in both virgin and recycled materials. It is therefore important to set high requirements for the products procured by the regions to ensure they do not contain environmentally or health-hazardous substances, and that suppliers can guarantee their products are free from unwanted chemicals.

The national circular economy strategy presented by the Swedish Government in July 2020 outlines the direction for the work needed to transition to circular production, consumption, and business models, as well as non-toxic and circular material cycles. The vision is a society where resources are used efficiently in non-toxic circular flows, replacing the need for virgin materials.

Illustration: Government Offices of Sweden

In the strategy’s focus area 2: Circular Economy through Sustainable Consumption and Use of Materials, Products, and Services, it is noted that public procurement holds significant potential to contribute to reduced emissions and to promote both the supply and demand of innovative, circular, and climate-smart solutions (200814_ce_webb.pdf (government.se)).

In April 2022, the first so-called gap analysis by the organisation Circle Economy was published, mapping Sweden’s circular economy. The analysis shows that Sweden is currently only 3.4 percent circular, compared with the global average of 8.6 percent (circularity-gap-report-sweden.pdf (resource-sip.se)).

The results indicate that there is considerable potential for further development to advance the transition to a circular economy in Sweden.